The ambitious dream of creating self-sufficient cities in space, envisioned by physicist Gerard K. O’Neill, has faced significant challenges as reality sets in. O’Neill, a professor at Princeton University, believed that by the early 21st century, humanity would thrive in vast cylindrical habitats orbiting Earth. His vision gained traction in the 1970s, but as of 2025, only a limited number of people—primarily astronauts—have lived in space, notably aboard the International Space Station.

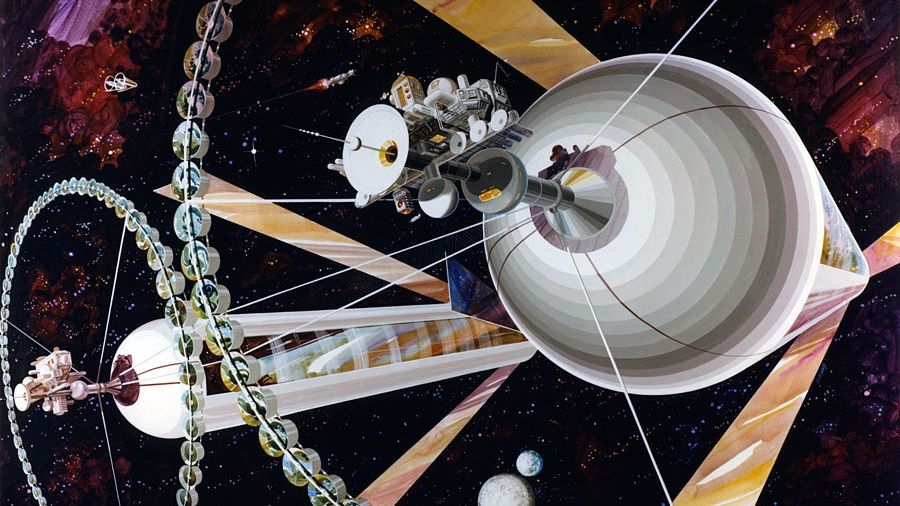

O’Neill’s ideas were articulated in his influential book, “The High Frontier,” published in 1976. He proposed the construction of large space habitats located at the gravitationally stable L5 Lagrange point between Earth and the moon. His most ambitious design, known as “Island Three,” would accommodate millions of residents in a space measuring four miles (6.4 kilometers) wide and 20 miles (32 kilometers) long. This concept captured public imagination, leading to the formation of the L5 Society, which famously aimed for “L5 by ’95.”

The underlying principle of O’Neill’s design was the use of rotation to generate a centrifugal force that would simulate gravity. He envisioned a variety of habitats, including cylindrical and spherical models, complete with 500 square miles (1,294 square kilometers) of living space filled with parks, recreational areas, and residential units. The concept even inspired elements of popular science fiction, such as the Babylon 5 space station.

Despite the grand scale of his vision, various factors hindered its realization. O’Neill suggested that industry and agriculture could operate in separate, smaller cylinders, with easy commuting facilitated by “commuterspheres” powered by electric motors. He estimated the cost of building such a habitat at around $200 billion in the 1970s, equivalent to approximately $1.1 trillion today.

O’Neill’s optimism stemmed from the technological advancements of the era, particularly following the success of the Apollo program. However, he faced increasing skepticism as the years progressed. The Club of Rome’s 1972 report, “Limits to Growth,” painted a grim picture of overpopulation and resource depletion, which O’Neill aimed to counteract by advocating for off-planet living.

The critical turning point came with the failure of the space shuttle program, which did not fulfill its initial promise of regular space travel. The shuttle’s limited operational capacity—135 flights from 1981 to 2011—left a significant gap in the infrastructure needed for large-scale space habitation. As a result, the ambitious projects O’Neill envisioned remained largely unattainable.

O’Neill’s concepts also faced scrutiny regarding their feasibility. Although the technology for constructing space habitats was theoretically within reach, practical implementation proved elusive. The challenges associated with creating a viable biosphere for millions of inhabitants, alongside the social implications of access to such habitats, raised difficult questions.

As humanity confronts pressing issues on Earth, including climate change, warfare, and inequality, O’Neill’s vision serves as a reminder of the potential for human ingenuity in space exploration. Despite the obstacles, proponents argue that space habitats could offer refuge from global crises and ensure the long-term survival of humanity.

Reflecting on O’Neill’s aspirations reveals a stark contrast to the current global landscape. The optimism of the 1970s, marked by visions of technological progress and exploration, has given way to a more complex reality. The question remains: did we fail the future, or did the future fail us?