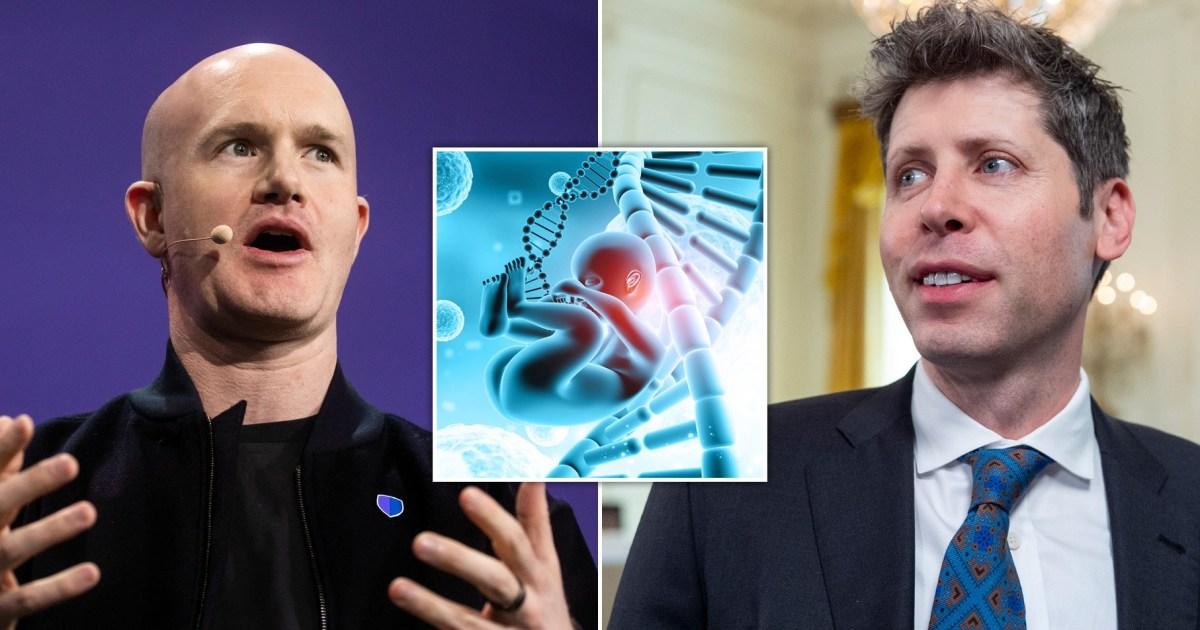

The emergence of a Silicon Valley startup, Preventive, marks a significant step toward the potential birth of genetically engineered babies. Founded by gene-editing scientist Lucas Harrington in San Francisco earlier this year, the company aims to eliminate hereditary diseases through human embryo editing. With an impressive funding of $30 million raised from prominent investors, including Brian Armstrong of Coinbase and Sam Altman of OpenAI, Preventive is poised to explore the uncharted territory of genetic modification.

Preventive is classified as a public benefit corporation, focusing on ensuring that the technology is both safe and transparent before any efforts are made to produce genetically modified children. Harrington emphasizes the enormous responsibility that comes with embryo editing, stating, “Embryo editing has tremendous potential advantages, including precision, efficiency, and cost.” He acknowledges, however, that careful research and regulatory oversight are essential to mitigate risks.

In a recent post on X, Harrington expressed his belief in the technology’s promise, claiming that, if proven safe, it could represent one of the most significant health advancements of our time. He also highlighted the risks of unregulated experimentation, saying, “Unfortunately, the combination of limited expert involvement and lack of a clear regulatory pathway has instead created conditions for fringe groups to potentially take dangerous shortcuts that could harm patients and stifle responsible investigation.”

The involvement of tech billionaires has drawn attention to the ethical complexities of this endeavor. Armstrong noted the impact of genetic diseases on over 300 million people globally, advocating for foundational research to explore safe therapies that could prevent such conditions at birth. He stated, “It is far easier to correct a smaller number of cells before disease progression occurs, such as in an embryo.”

This initiative echoes the controversial actions of Chinese scientist He Jiankui, who garnered global outrage after creating the first gene-edited babies in 2018. Jiankui’s experiments led to a three-year prison sentence for illegal medical practices, prompting calls from researchers around the world for a temporary halt on germline editing. Since then, U.S. senators have sought to establish international standards for germline gene editing to prevent unethical practices that could arise in countries with looser regulations.

In the United States, the landscape for research on human germline gene therapy is complex. While federal law prohibits the use of government funds for this type of research, private funding is still permissible. This means that laboratories could conduct non-clinical human gene therapy research, but any therapy intended for sale would require approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before it could enter clinical trials.

Despite the potential benefits of gene editing—such as preventing hereditary diseases—ethical concerns loom large. Critics argue that altering embryos could have unforeseen consequences for future generations. Moreover, the individuals most affected by these decisions, the unborn children, cannot express their consent. This raises profound questions about autonomy and the moral implications of genetic modification.

As Preventive continues its mission, the tension between innovation and ethical responsibility remains a focal point in the debate over the future of genetic engineering. The company’s progress will likely shape discussions within the scientific community and beyond, as stakeholders grapple with the implications of creating genetically engineered humans.