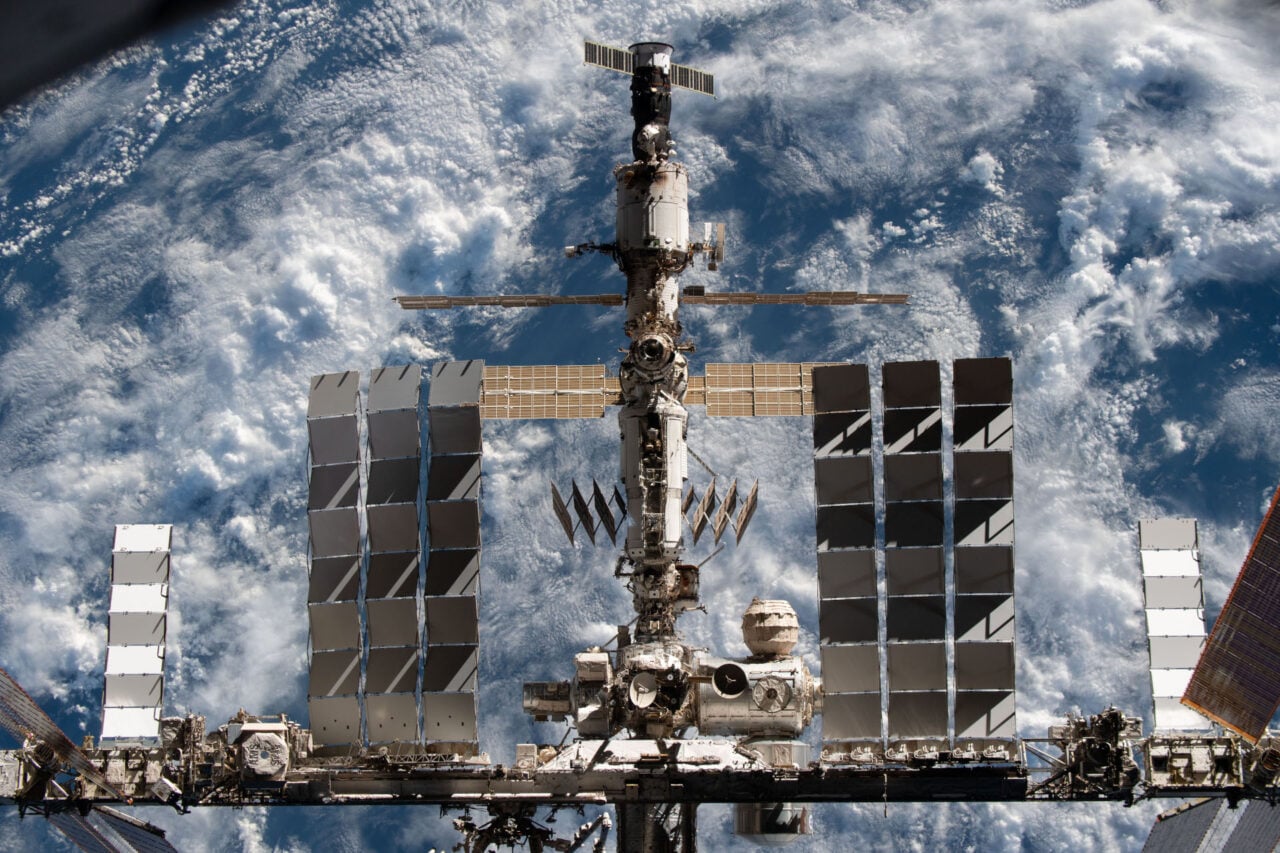

Research conducted aboard the **International Space Station (ISS)** has revealed that bacteriophages, the viruses that infect bacteria, exhibit unusual behaviors in microgravity. A team of scientists studied the interactions between **T7 phages** and **Escherichia coli** bacteria in space, discovering that these phages took longer to initiate infection compared to their Earth-based counterparts. Additionally, both the viruses and bacteria underwent unexpected mutations in response to the unique conditions of space.

The study, published on **March 15, 2024**, in **PLOS Biology**, highlights how microgravity alters the fundamental processes of microbial evolution. Senior study author **Vatsan Raman**, a biomolecular and cellular engineer at the **University of Wisconsin–Madison**, emphasized that these findings challenge previous assumptions about microbial behavior in space. He stated, “Microbes continue to evolve under microgravity, and they do so in ways that are not always predictable from Earth-based experiments.”

Unusual Interactions in Microgravity

Historically, research has shown that various microbes can thrive aboard the ISS, including those left behind by astronauts. Despite this, Raman pointed out that limited studies have focused on how phages and the bacteria they infect interact in such an environment. “Most microbial evolution experiments implicitly assume Earth-like physical conditions,” he explained. “Spaceflight changes fundamental aspects of the environment—how fluids mix, how cells encounter one another, and how physical forces shape cellular physiology.”

The research specifically examined the behavior of T7 phages, which are known to infect E. coli. According to the findings, these phages initially experienced delays in infecting their bacterial hosts, likely due to the altered fluid dynamics in microgravity. Once infection commenced, both the phages and bacteria adapted rapidly, often diverging significantly from their terrestrial counterparts. The bacteria developed defenses against phage attacks while the phages evolved mechanisms to enhance their infectivity.

Raman noted, “The main takeaway is that microgravity doesn’t just delay phage infection—it reshapes how phages and bacteria evolve together.” The researchers observed mutations in unexpected genes that are typically not characterized in standard laboratory settings, indicating a profound shift in microbial dynamics due to space conditions.

Implications for Space Travel and Human Health

The study’s implications extend beyond scientific curiosity; they have significant relevance for future space missions. The evolution of microbes aboard the ISS may influence astronaut health and environmental stability in long-duration missions. Raman cautioned that these microbes are not merely passive inhabitants; they could evolve in ways that pose risks to human health.

Conversely, the research underscores the potential benefits of space-adapted phages in combating drug-resistant infections on Earth. The team found that mutations observed in the ISS phages improved their ability to target T7-resistant E. coli strains, which are known to cause urinary tract infections in humans.

Phage therapy is gaining traction as a promising alternative treatment for antibiotic-resistant infections. Despite the logistical challenges of conducting similar experiments in space, understanding how microgravity influences microbial evolution could yield valuable insights applicable to Earth-based studies.

Raman expressed hope that this research will inspire scientists to view space as a distinct environment that can reveal new biological insights. “I hope this work encourages researchers to think of space not just as a place to reproduce Earth experiments, but as a fundamentally different physical environment that can uncover new biology,” he said.

Looking ahead, the research team aims to investigate the specific genes and mutations in T7 phages that arise under microgravity conditions. They also plan to explore how space can alter the biology of more complex microbial communities, furthering our understanding of life beyond Earth.