Researchers at Kyoto University have identified a brain pathway that may provide insights into treating severe motivational deficits observed in conditions such as depression and schizophrenia. The study, published in Current Biology, reveals how a specific circuit in the brain acts as a “motivation brake,” impacting an individual’s ability to initiate tasks, particularly when faced with unpleasant or stressful situations.

The research team, led by Ken-ichi Amemori, PhD, an associate professor at the Institute for the Advanced Study of Human Biology, utilized advanced genetic techniques known as chemogenetics on trained macaque monkeys. By manipulating communication between the ventral striatum (VS) and ventral pallidum (VP), the scientists were able to observe how this circuit regulates motivation under adverse conditions.

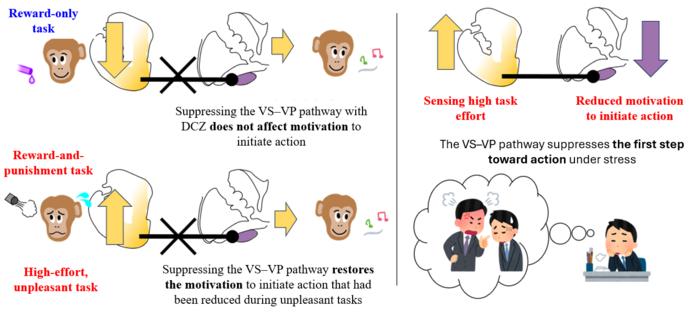

Avolition, characterized by the inability to initiate actions despite knowing what needs to be done, is a common symptom in psychiatric disorders such as major depressive disorder (MDD) and schizophrenia. This phenomenon can severely disrupt daily life and social functioning. The researchers found that when the VS–VP pathway was suppressed, the monkeys demonstrated a restored capability to act in scenarios where stress was a factor, revealing the pathway’s significant role as a motivational regulator.

The experiments involved two types of tasks for the macaques: one where completing the task yielded a reward, and another where the reward was accompanied by an unpleasant stimulus. The results indicated that while the monkeys performed well on the reward-only tasks, their motivation waned significantly when the tasks also involved a punishment. This drop in motivation was alleviated when the VS–VP pathway was inhibited, allowing the monkeys to overcome the mental barriers that typically hinder action initiation.

In their findings, the researchers highlighted that the VS and VP are critical components of the brain’s motivational regulation system. The VS is essential for processing rewards and driving motivation, while the VP contributes to goal-directed behavior. Understanding how these areas interact provides a deeper insight into the neural mechanisms that govern motivation, particularly when negative stimuli are present.

The study’s authors concluded that their findings could lead to new treatment approaches for individuals suffering from motivational deficits. They proposed potential interventions, such as deep brain stimulation or noninvasive brain techniques, aimed at fine-tuning the motivation brake when it becomes overly restrictive. “From a clinical perspective, these findings provide mechanistic insight into motivational deficits central to psychiatric disorders,” the researchers noted.

While recognizing the potential for therapeutic applications, Amemori cautioned against over-weakening the motivational brake, as this could lead to risk-taking behaviors or burnout. Striking a balance is crucial, as an adequately functioning motivation system is vital for maintaining healthy behavior.

These discoveries prompt a reevaluation of how motivation is understood in modern society. Instead of merely focusing on willpower to overcome challenges, there is an increasing need to consider how societal factors can support individuals in managing stress and enhancing motivation. The implications of this research extend beyond the lab, inviting broader discussions on mental health and the importance of supportive environments in promoting psychological well-being.

As scientists continue to explore the complexities of motivation, the potential to transform treatment strategies for debilitating conditions such as depression and schizophrenia remains an exciting frontier in neuroscience.