A recent study reveals that two groups of Neanderthals, inhabiting the Amud and Kebara caves in northern Israel, butchered their prey in notably different ways. This finding suggests the existence of local food traditions among these ancient populations, despite their proximity and shared resources.

According to the research published in Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology, the two caves, located just 70 kilometers apart, were occupied by Neanderthals during the winters between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago. The study, led by Anaëlle Jallon, a Ph.D. candidate at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, indicates that these groups, while utilizing similar tools and prey, developed distinct butchery practices that may have been passed down through social learning.

“The subtle differences in cut-mark patterns between Amud and Kebara may reflect local traditions of animal carcass processing,” Jallon noted. She emphasized the importance of this research in understanding whether Neanderthal butchery techniques were standardized or influenced by factors such as cultural traditions or social organization.

Examining the remains of hunted animals, researchers found that the Neanderthals at Kebara primarily targeted larger prey compared to those at Amud. Notably, the Kebara group appears to have transported larger kills back to the cave for butchering, while the Amud group left behind a higher percentage of burned and fragmented bones—40% compared to Kebara’s 9%. This could indicate differences in cooking methods or later damage from carnivores.

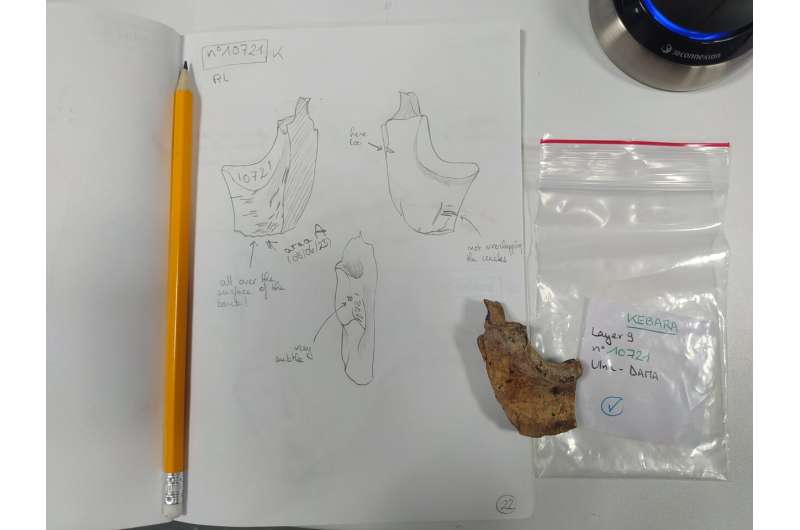

To investigate these butchering differences, scientists analyzed a sample of cut-marked bones from both sites. By examining the characteristics of these marks, they aimed to identify patterns that could indicate variations in butchering practices. The results revealed that while the tools used were similar, the cut-marks at Amud were denser and less linear than those at Kebara.

The researchers considered several factors that could explain these variations. One possibility is that the Neanderthals at Amud had different pre-butchering practices, such as drying or allowing meat to decompose, akin to modern techniques used by butchers. Alternatively, differences in group organization, such as the number of individuals involved in butchering, might also have influenced these patterns.

Jallon acknowledged the limitations of the study, noting that some bone fragments were too small to provide a complete understanding of the butchery marks. “While we have made efforts to correct for biases caused by fragmentation, this may limit our ability to fully interpret the data,” she said. Future research, including experimental work and comparative analyses, will be essential to address these uncertainties and potentially reconstruct Neanderthal food preparation practices.

This study sheds light on the complexities of Neanderthal life and suggests that even subsistence activities like butchering were influenced by cultural elements. Further exploration of these ancient practices could enhance our understanding of Neanderthal social structures and their adaptation strategies in a challenging environment.