In the 1240s, Richard Fishacre, a Dominican friar at the University of Oxford, made significant contributions to astronomy by challenging prevailing beliefs about the composition of stars and planets. He asserted that these celestial bodies are made from the same elements found on Earth, a claim that predated modern discoveries by centuries, including those made by the James Webb Space Telescope.

Medieval thought, heavily influenced by the Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, posited that stars and planets were composed of a unique celestial element known as the “fifth element” or “quintessence.” This element was believed to be perfect and unchanging, forming the basis of nine concentric celestial spheres, with each sphere housing its own planet. The outermost spheres were thought to contain the stars and heaven itself.

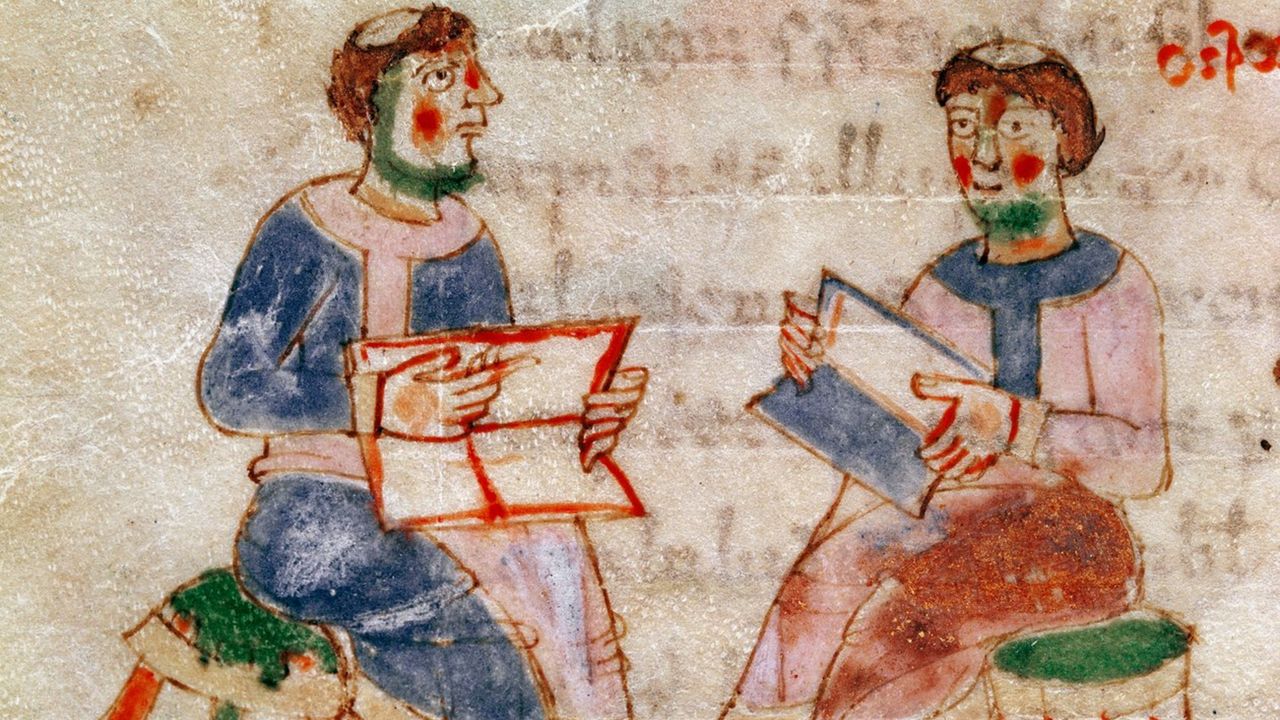

Fishacre rejected this notion. As the first Dominican friar to teach theology at Oxford, he argued that the stars and planets were instead made from the same four terrestrial elements: fire, water, earth, and air. His reasoning stemmed from a keen understanding of light and color.

Color and Light in Astronomy

Fishacre observed that color is typically associated with opaque bodies, which are always composed of two or more of the four elements. Observing the stars and planets, he noted the faint colors emitted—Mars appearing red and Venus yellow—suggesting they too were composite bodies made “ex quattuor elementis,” or “out of the four elements.”

He identified the moon as a key piece of evidence. The moon exhibits a distinct color and, during an eclipse, blocks sunlight. If the moon were made of the transparent fifth element, light would pass through it, similar to a pane of glass. This observation led Fishacre to conclude that both the moon and Earth share the same elemental composition, extending this reasoning to all celestial bodies.

Fishacre recognized the risk of backlash for his revolutionary ideas. He foresaw criticism from those adhering to Aristotelian principles. “If we posit this position,” he wrote, “then they, that crowd of Aristotelian know-it-alls, will cry out and stone us.” His fears were realized when, in 1250, his teachings were condemned at the University of Paris by St. Bonaventure, a Franciscan friar who derided those who questioned Aristotle’s teachings.

Despite facing significant criticism, Fishacre’s assertions have gained validation through contemporary astrophysics. Modern astronomy has confirmed that stars and planets are not composed of a unique fifth element but of elements similar to those found on Earth. For example, the James Webb Space Telescope recently detected significant amounts of water and sulfur dioxide in the atmosphere of the exoplanet TOI-421 b, located approximately 244 light-years away.

The method used by the James Webb, known as transmission spectroscopy, mirrors Fishacre’s approach. It detects subtle variations in light’s brightness and color, allowing scientists to identify the elemental make-up of distant celestial bodies.

Fishacre’s legacy endures, as contemporary astronomy continues to utilize light and color in its investigations. Nearly 800 years after his death, his pioneering work laid the groundwork for modern understandings of the universe, demonstrating that the same fundamental elements comprise both our planet and the stars above.