On December 26, 1898, chemists Marie Curie, Pierre Curie, and Gustave Bémont announced their groundbreaking discovery of two highly radioactive elements, radium and polonium, in Paris. This work not only advanced scientific understanding of radioactivity but also set the stage for significant medical innovations—albeit with tragic consequences for Curie herself.

The Spark of a Revolutionary Idea

At the time of her discovery, Marie Curie was a medical student at the Sorbonne. She chose to focus her thesis on the emerging field of radiation, inspired by earlier discoveries such as Wilhelm Röntgen‘s X-rays in 1895 and Henri Becquerel‘s accidental identification of rays emitted by uranium salts the following year. These discoveries piqued her curiosity and motivated her to conduct her own experiments.

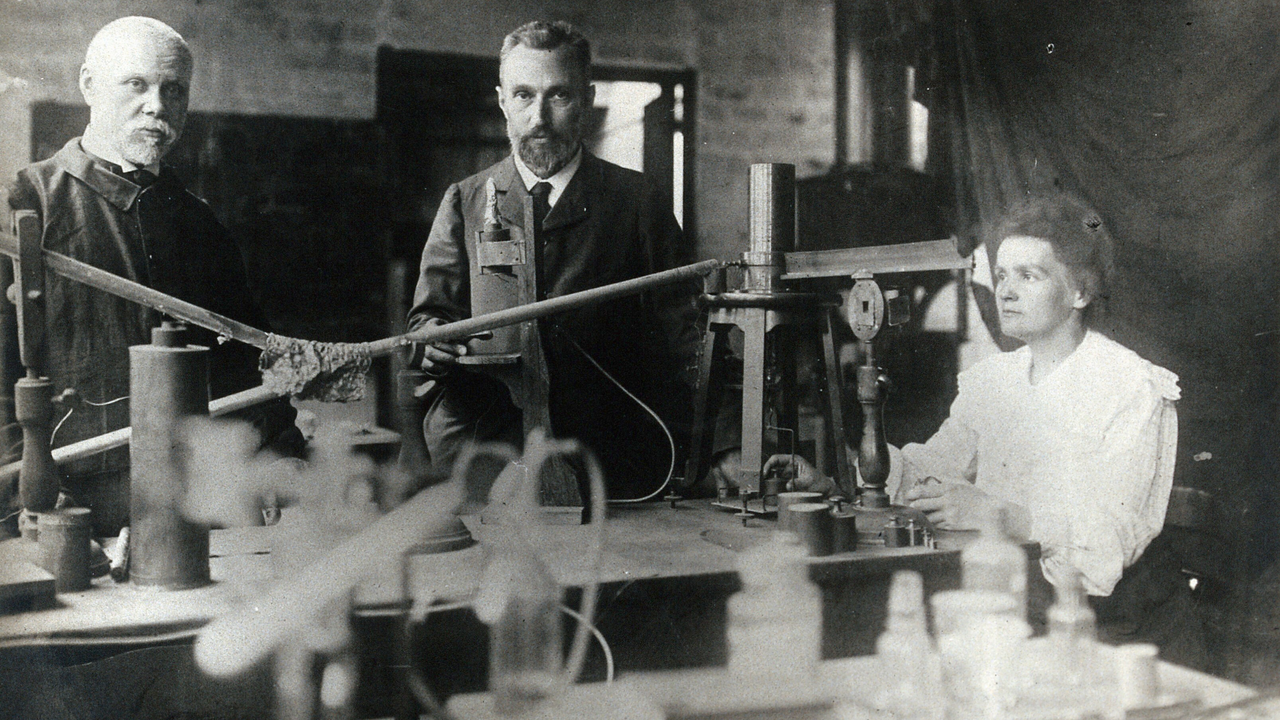

Curie worked in a small, cluttered storeroom at the Paris Municipal School of Industrial Physics and Chemistry, where her husband Pierre provided a workspace. As they delved deeper into their research, Pierre became fascinated with his wife’s work, eventually abandoning his own studies to assist her.

Unveiling the Mystery of Radioactivity

Central to the Curies’ research was the piezoelectric quartz electrometer, a device invented by Marie’s brother-in-law, Jacques Curie. This instrument measured the weak electric currents generated by radioactive materials. In a 1904 article for Century magazine, Marie expressed her preference for measuring radiation intensity through air conductivity rather than relying solely on photographic plates.

Despite challenges posed by the damp environment of their workspace, Curie discovered that the intensity of radiation was linked to the uranium concentration in the minerals she examined. This finding led her to hypothesize that a substance more radioactive than uranium existed within the mineral pitchblende, which was abundant in uranium deposits.

Working alongside her husband and Gustave Bémont, the trio began separating pitchblende into its components. Their efforts culminated in the identification of polonium in July 1898, which was approximately 60 times more radioactive than uranium. Just days later, they isolated radium, an astonishing 900 times more radioactive than uranium.

On December 26, 1898, they presented their findings to the French Academy of Sciences, marking a pivotal moment in scientific history. The Curies would continue their work, ultimately earning the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903, although Marie was initially overlooked until Pierre insisted on her acknowledgment.

Legacy and Consequences

Marie Curie’s pioneering research laid the groundwork for modern medicine, particularly in the field of radiotherapy for cancer treatment. Following her husband’s tragic death in 1906, Curie remained committed to advancing scientific knowledge, advocating for the use of X-rays in medical applications during World War I. She developed mobile X-ray units to assist wounded soldiers on the battlefield.

Despite her remarkable contributions, the dangers of radiation exposure became evident. Both Curies suffered from radiation sickness, and Marie’s prolonged exposure ultimately contributed to her death from aplastic anemia in 1934, at the age of 66. Today, the notebook containing her original discovery notes remains radioactive and is stored in a lead box, a testament to her enduring legacy and the profound impact of her work on science and medicine.