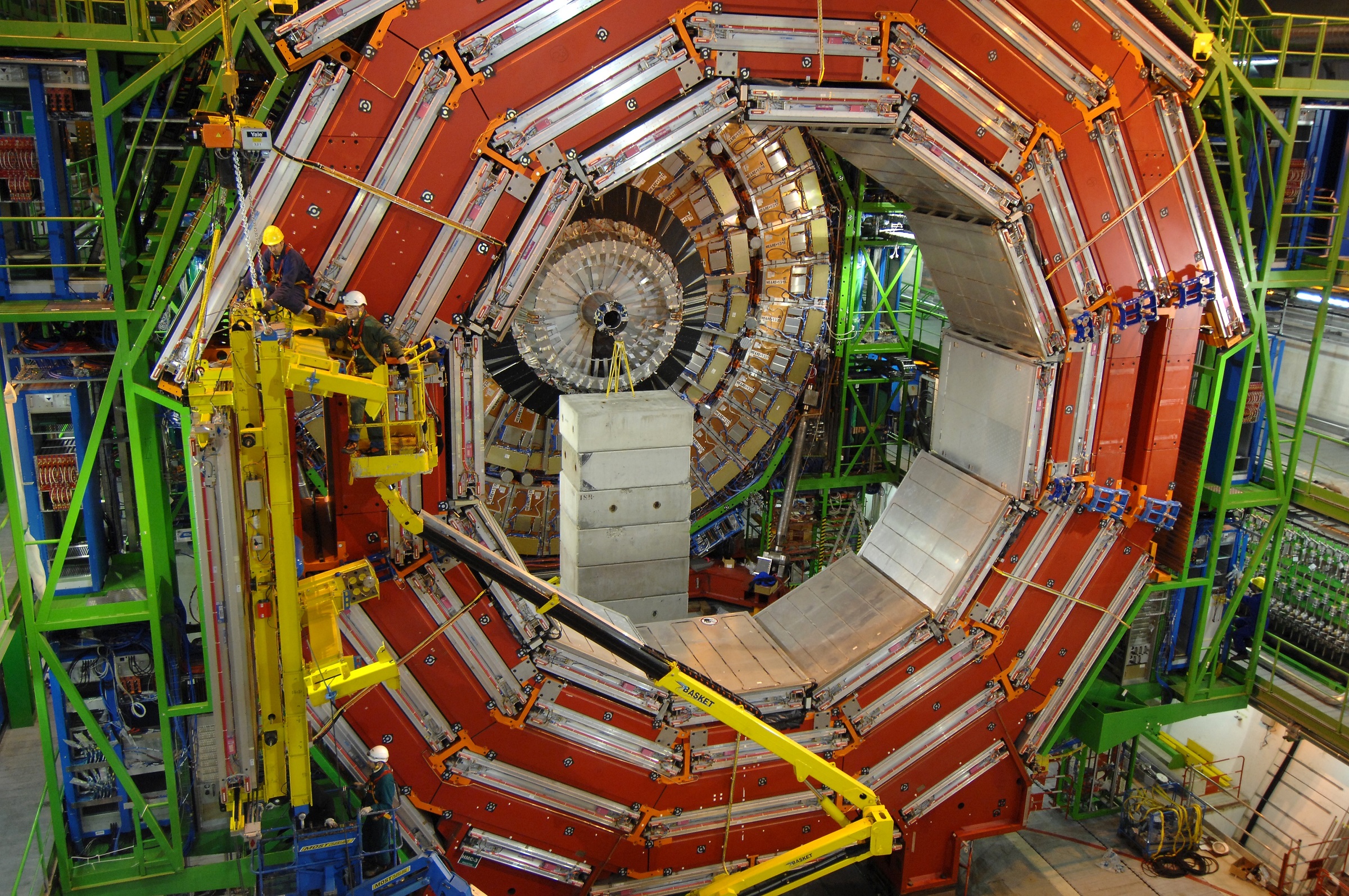

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC), located in a 16-mile underground tunnel near the Swiss-French border, will undergo a significant upgrade starting in June, leading to a temporary shutdown of operations. This pause is intended to enhance the device’s capabilities, allowing for ten times the number of particle collisions it currently facilitates. The project, known as the high-luminosity LHC, is scheduled to take approximately five years, with the collider expected to resume operations around mid-2030.

Originally designed to recreate the extreme conditions of the early universe shortly after the Big Bang, the LHC has been instrumental in pivotal discoveries, including the identification of the Higgs boson in 2012. This particle plays a crucial role in giving mass to other particles through complex quantum interactions. Despite the impending hiatus, Mark Thomson, the new director general of CERN, emphasized the wealth of data already collected.

“The machine is running brilliantly, and we’re recording huge amounts of data,” said Thomson, who began his term on January 1. He assured that physicists would have plenty to analyze during the downtime, stating, “The physics results will keep on coming.”

The high-luminosity upgrade aims to facilitate more experiments and generate additional data, a process that Thomson described as “incredibly exciting.” His leadership coincides with discussions about the LHC’s future successor, the proposed Future Circular Collider (FCC). This ambitious project, envisioned to be 56 miles in circumference, would dwarf the current LHC and aims to advance particle physics even further.

However, the FCC’s future is uncertain, primarily due to its estimated cost of nearly €19 billion, which CERN cannot cover alone. There are also ongoing debates regarding the efficacy of large particle accelerators in addressing fundamental questions about dark matter and dark energy. Despite these challenges, Thomson remains optimistic about the future of particle physics.

“We’ve not got to the point where we have stopped making discoveries, and the FCC is the natural progression. Our goal is to understand the universe at its most fundamental level,” he noted. “And this is absolutely not the time to give up.”

As the LHC prepares for its extensive refurbishment, the scientific community looks ahead, balancing the excitement of potential breakthroughs with the reality of a lengthy operational pause.

In the meantime, CERN continues to analyze the vast amounts of data already collected, ensuring that the LHC’s legacy of discovery persists even during its temporary downtime.