Last summer, a great white shark washed ashore in Nantucket, Massachusetts. A vacationing family encountered the stranded predator flailing in the shallow waves and made an unexpected decision. They cautiously approached and pushed the shark back into the ocean, capturing a viral moment that was both heartwarming and perilous.

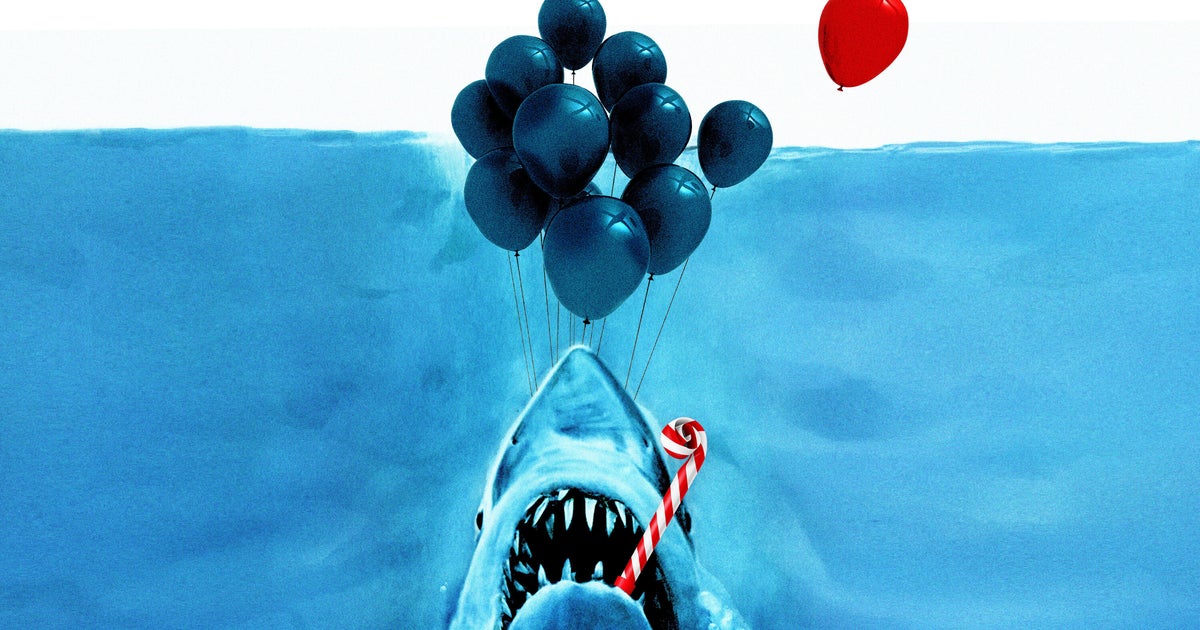

Fifty years ago, during the summer “Jaws” first terrified audiences in theaters, such an encounter might have ended very differently. On June 20, 1975, Steven Spielberg’s “Jaws” debuted, creating the modern blockbuster and igniting a global fascination—and fear—of sharks. According to the American Film Institute, it was the first film to earn more than $100 million at the U.S. box office. Based on Peter Benchley’s best-selling novel, “Jaws” not only sparked interest in studying these ancient predators but also fueled a craze for hunting them as trophies.

“When ‘Jaws’ came out, there was an uptick in shark tournaments,” said Wendy Benchley, ocean conservationist and wife of the “Jaws” author. “This fictional book and movie somehow gave people the license to kill sharks.”

In the half-century since, our understanding of great white sharks has grown immensely, yet much remains unknown about these ocean rulers. Meanwhile, global shark populations have plummeted due to overfishing, even as sightings and attacks have increased along the U.S. East Coast, a phenomenon scientists are still unraveling.

The Impact of ‘Jaws’

The release of “Jaws” had a profound impact, both culturally and ecologically. Wendy Benchley recalls her first scuba dive after seeing the film, admitting it left her apprehensive. The movie tapped into a primal fear of being consumed by a monstrous fish, a fear that resonated deeply with audiences worldwide.

“‘Jaws’ touched our innate fear of being eaten by a monster fish,” she remarked. “I’m not dismissing the fact that it is a very real, visceral fear for people.”

Robert Shaw’s portrayal of the gruff shark hunter Quint inspired many fans to partake in shark-hunting tournaments. The number of recorded great whites caught and killed spiked in the three years following the film’s release. Steven Spielberg himself expressed regret over the unintended consequences of “Jaws” on shark populations.

“I truly and to this day regret the decimation of the shark population because of the [‘Jaws’] book and the film,” Spielberg confessed on BBC Radio 4’s “Desert Island Discs” in 2022.

Yet, the film also had positive repercussions. It inspired a new generation of marine scientists, akin to Richard Dreyfuss’ character, Matt Hooper. Enrollment at the Rosenstiel School of Marine Science at the University of Miami reportedly increased by 30% as a result.

Shark Populations on the Decline

While “Jaws” may not be solely responsible, the global shark population has significantly declined since the film’s release. A 2021 report in the journal Nature highlighted a 71% drop in the number of sharks and rays since 1970, largely due to an 18-fold increase in fishing.

“We only have 10% of the sharks left that we had in the ocean 40 years ago,” Wendy Benchley noted.

Overfishing, driven by massive ships that indiscriminately sweep the ocean, and the demand for shark fin soup in China and other Asian countries have contributed to this decline. WildAid, a wildlife nonprofit, has successfully reduced demand for shark fin soup by 85% through campaigns featuring celebrities like Yao Ming and Jackie Chan.

“You’ve got to have apex predators in the ocean to keep the ecosystem in balance,” Benchley emphasized.

Are Shark Attacks on the Rise?

Globally, shark attacks are not increasing. The International Shark Attack File reported 47 unprovoked bites in 2024, down from an annual average of 64. However, along the U.S. East Coast, sightings and bites are rising. Florida remains the most likely place for shark encounters, with 14 bites recorded in 2024. A 2023 attack on Rockaway Beach in Queens marked New York’s first such incident since the 1950s.

The resurgence of sharks in these areas is attributed to the recovery of seal populations, their natural prey, thanks to conservation efforts. Climate change may also play a role, as warmer oceans attract marine life that, in turn, draws hungry sharks.

“There are more great white sharks along the East Coast, and that is an environmental success story,” Benchley stated. “Sharks do not like humans. We don’t have enough fat on us. They’d much rather have a seal.”

Nevertheless, Benchley advises swimmers to exercise caution: stay in shallow waters, avoid swimming at dawn or dusk, and steer clear of seals.

The Legacy of ‘Jaws’

“Jaws” leaves behind a complex legacy. While it incited a wave of shark hunting, it also inspired scientific inquiry and conservation efforts. Benchley finds solace in the fact that, 50 years later, bystanders in Nantucket chose to save a beached shark rather than harm it. For someone whose husband instilled a fear of the ocean, yet dedicated her life to its preservation, this represents a significant victory.

“Thank heavens,” she said. “People finally understand how vital sharks are.”