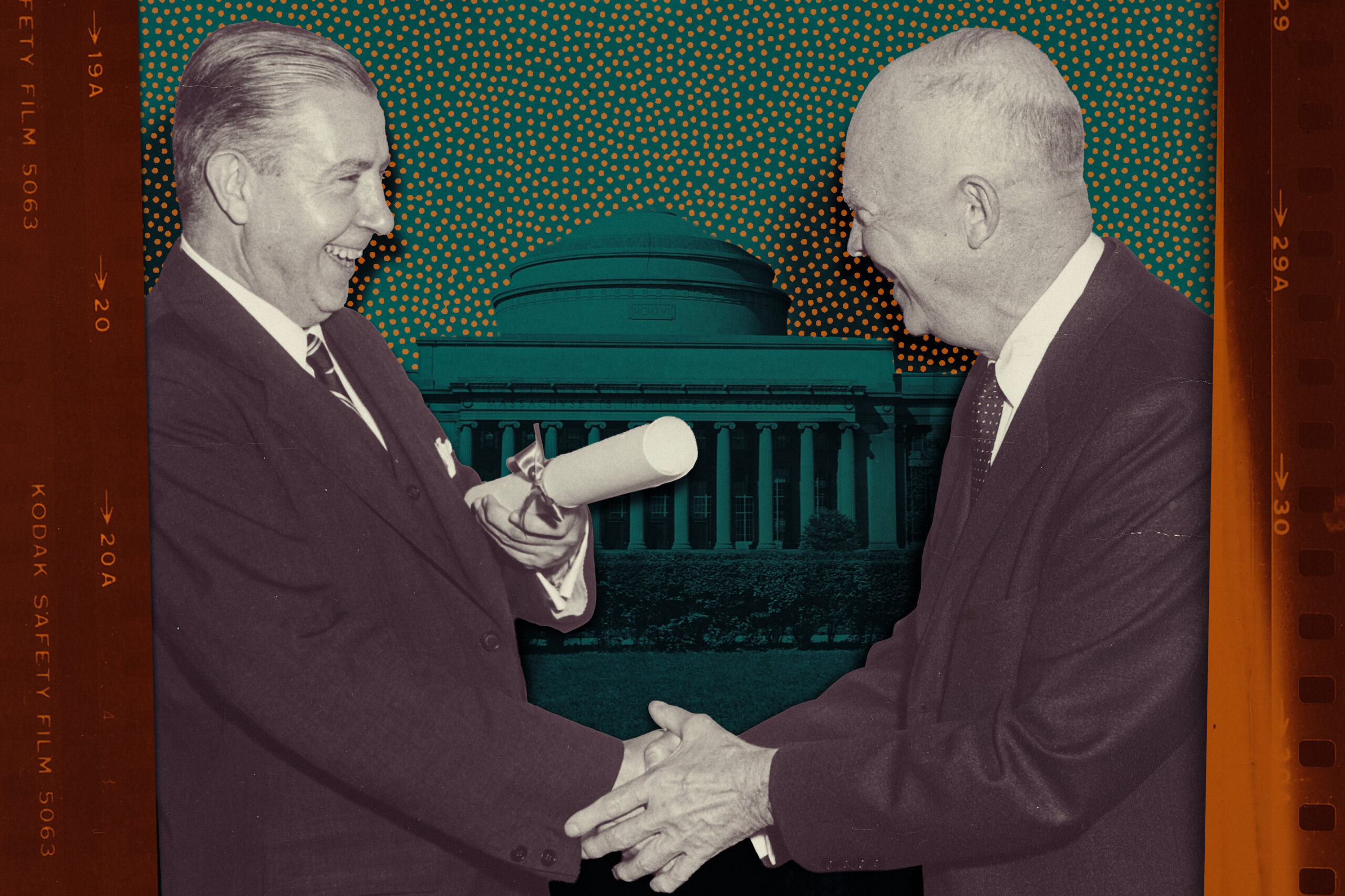

In a pivotal moment during the Cold War, James Killian, the 10th president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), significantly shaped U.S. national security strategies. His leadership came at a time when the 1953 intelligence report revealed that the USSR had successfully tested a nuclear bomb earlier than anticipated, escalating fears of a surprise nuclear attack on American soil. President Dwight Eisenhower, grappling with these revelations, sought Killian’s expertise to navigate the emerging complexities of the Cold War.

Killian’s Ascendancy and Contributions

Killian’s journey to the presidency of MIT was unconventional; he was not a scientist or engineer but an adept administrator. David Mindell, the Dibner Professor of the History of Engineering and Manufacturing at MIT, commented, “Killian turned out to be a truly gifted administrator.” His previous roles, including leading the RadLab during World War II, positioned him uniquely to understand the intersection of technology and national defense.

In 1951, he established the MIT Lincoln Laboratory, a federally funded research centre focused on developing air defense technologies to counter nuclear threats. Following Eisenhower’s request in 1953, Killian gathered a team of prominent scientists to assess U.S. military capabilities. Their findings culminated in the Killian Report, delivered to Eisenhower on February 14, 1955.

This comprehensive 190-page document outlined critical assessments of U.S. offensive capabilities, continental defense, and intelligence operations. Over a span of months, the team conducted 307 meetings with major defense and intelligence organizations, gaining unrestricted access to national defense projects.

Strategic Insights and Legacy

The Killian Report highlighted the shifting balance of power between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. It projected that while the U.S. held a significant offensive advantage in 1955, it remained susceptible to surprise attacks. The report emphasized the necessity for accelerated development of intercontinental ballistic missiles and enhanced air defense systems.

“Eisenhower really wanted to draw the perspectives of scientists and engineers into his decision-making,” Mindell noted, reflecting on the report’s impact.

The document also initiated a new era in the relationship between the federal government and academic institutions. Eisenhower circulated the Killian Report to heads of all federal departments, seeking their input on its recommendations. This marked the beginning of a collaborative relationship between scientists and policymakers, significantly influencing U.S. defense strategies during the Cold War.

Killian’s innovative approach extended beyond the report’s publication. He recruited Edwin Land, co-founder of Polaroid, to lead the intelligence panel. Land’s unique insights and experience in military technology helped refine U.S. intelligence operations. Killian and Land proposed the development of missile-firing submarines and the rapid deployment of the U-2 spy plane, both of which played critical roles in U.S. surveillance capabilities.

Despite its complexities, the Killian Report set a precedent for future governmental engagements with scientific communities. As Eisenhower faced increasing pressures regarding Soviet advancements, Killian’s contributions became even more vital. Following the launch of Sputnik, which sparked public concern over Soviet technological prowess, Eisenhower appointed Killian as the first special assistant to the president for science and technology.

Through this position, Killian facilitated the establishment of NASA and significantly influenced the Apollo mission, which ultimately achieved the historic goal of landing humans on the moon. His legacy remains evident in ongoing research at MIT and the Lincoln Laboratory, where advancements continue to support national security and technological leadership.

Reflecting on his experiences, Killian noted the dedication of scientists who served during a time of crisis, emphasizing their commitment to both the presidency and the nation. His ability to communicate effectively with Eisenhower distinguished him as one of the president’s most trusted advisors. “Killian could talk to the president, and Eisenhower really took his advice,” Christopher Capozzola, a historian, remarked, highlighting the rarity of such a relationship.

As the Cold War unfolded, the impact of the Killian Report was profound, fostering a new paradigm in defense policy shaped by scientific insight and collaboration. The relationship between academia and government not only evolved but also established a framework for addressing future challenges in national security, technology, and international relations.