In 1925, an unexpected breakthrough in cancer research emerged from an unlikely duo: a London hatter and a former railway clerk. Their findings, published in the prestigious medical journal The Lancet, were heralded as a significant event in medical history, with editors proclaiming the studies might offer solutions to the central problem of cancer. The announcement sparked a wave of excitement, drawing a crowd outside the journal’s office in London, eager to learn about the first glimpses of the cancer “germ” observed under a microscope.

As the 1920s unfolded, the field of bacteriology was flourishing. Scientists had successfully identified the bacteria behind diseases like cholera and tuberculosis. The public was primed for another groundbreaking discovery, especially regarding a disease as feared as cancer. What made this revelation stand out was the unconventional background of its researchers—Joseph Edwin Barnard, the hatter, and William Ewart Gye, a railway clerk—who were both outsiders to the formal medical establishment.

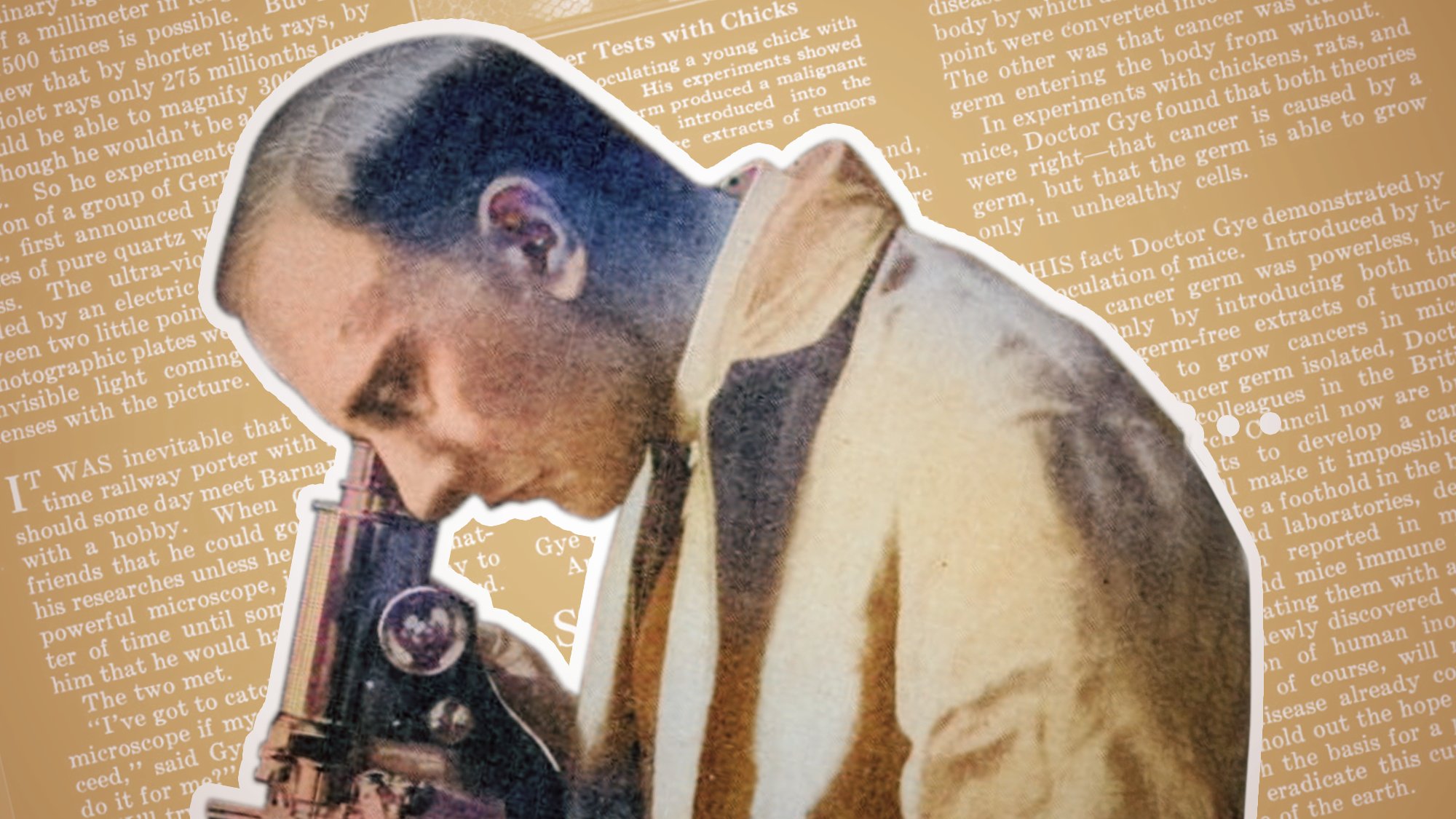

Barnard led a dual life, crafting hats by day at J. Barnard & Sons, a business founded by his father, and pursuing his passion for microbiology at night. His experiments involved innovative microscopy techniques, including ultraviolet light, allowing him to develop custom lenses that significantly enhanced visibility beyond conventional optics. This dedication enabled him to capture images of microorganisms with unprecedented clarity.

Gye’s path to this groundbreaking research was equally unconventional. Originally named William Ewart Bullock, he changed his surname in 1919, possibly to avoid confusion with a noted bacteriologist or as a tribute to his suffragette wife, Elsa Gye. The reasons behind this name change remain debated, adding an air of mystery to his persona. Nevertheless, Gye’s commitment to studying cancer was unwavering, supported by a benefactor who financed his education and research.

Together, Barnard and Gye formed a synergistic partnership. Gye brought extensive knowledge of experimental biology and germ theory, while Barnard’s expertise in microscopy provided the tools necessary to explore the intricacies of cancer. Their collaboration built upon decades of progress initiated by pioneers like Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur, who laid the groundwork for germ theory and vaccination.

The duo’s research culminated in the identification of “particulate bodies,” which Gye described as a potential cancer virus. This discovery, supported by Barnard’s meticulous imaging, suggested that cancer could be linked to a specific microorganism, a theory that captured the imagination of the scientific community. Gye proposed a two-factor theory of cancer, asserting that both a virus and a specific factor from tumor extracts were necessary for the disease to develop. His experiments demonstrated that tumors could only form when both elements were present, marking a significant departure from previous understandings of cancer.

As Gye shared his observations in The Lancet, he noted variations in cell wall thickness, suggesting that the virus replicated within the cells. This led to a hopeful anticipation that a cancer vaccine could soon be developed. Gye’s findings spurred further research within the British Medical Research Council, aiming to create a vaccine that would prevent cancer from taking hold in the body.

Although Gye’s two-factor theory was not wholly accurate, it provided crucial insights that shaped future cancer research. Today, the understanding of cancer has evolved significantly. Modern research recognizes the complexity of the disease, which is influenced by genetic mutations, environmental factors, and, in some cases, viruses like human papillomavirus (HPV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

Rather than searching for a single germ, contemporary cancer researchers utilize advanced technologies, including electron microscopes and super-resolution imaging, to investigate cellular structures and molecular pathways. The optimism surrounding Gye’s and Barnard’s findings laid the groundwork for ongoing advancements in cancer prevention, detection, and treatment.

While the challenge of fully solving cancer persists, the work of these two men reminds us of the importance of accessibility in scientific inquiry. Their story illustrates how passion and unconventional backgrounds can lead to transformative breakthroughs in medicine. The legacy of Joseph Edwin Barnard and William Ewart Gye continues to inspire researchers today as they navigate the complexities of cancer research in pursuit of effective treatments and potential cures.