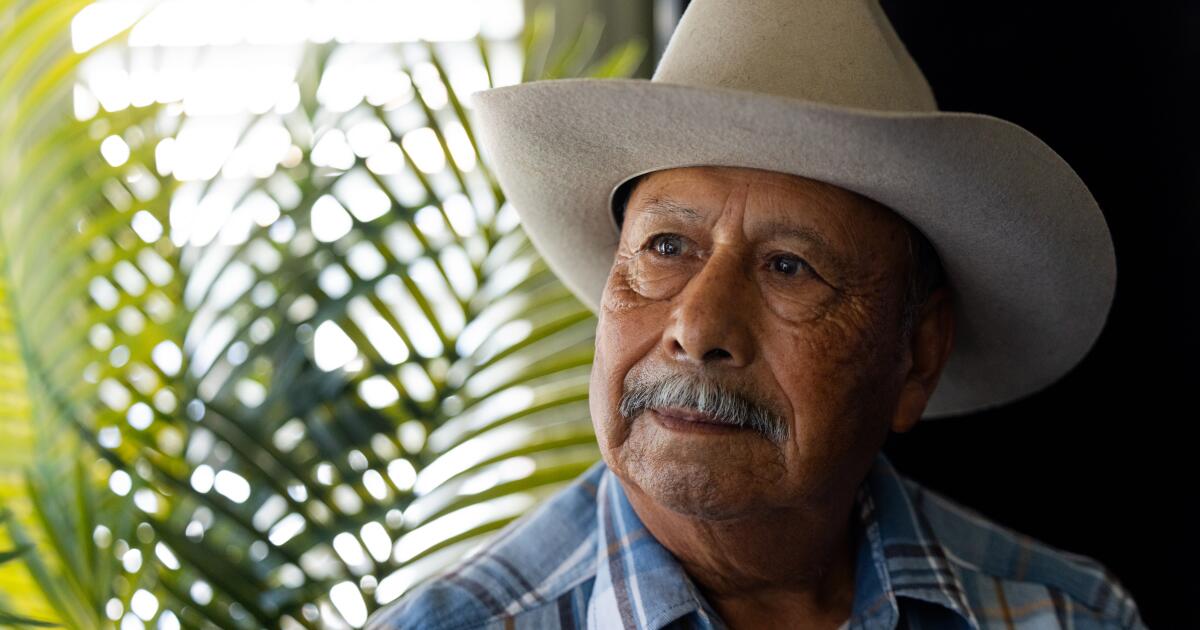

UPDATE: Former bracero Manuel Alvarado, now 85, has expressed grave concerns over potential plans to revive the Bracero Program, stating, “If that happens, those people will be treated like slaves.” His comments come amidst mounting discussions about agricultural labor shortages in the U.S., with officials seeking solutions.

Alvarado, who traveled from La Cañada, Zacatecas to the U.S. in 1961, recalls his own experiences under the program, which allowed over 2 million Mexican men to work legally in the United States. “The Bracero Program helped a lot of people,” he reflected, yet he firmly believes that restoring such a system today would lead to exploitation.

As farmers plead for labor amid ongoing deportations, Rep. Monica De La Cruz introduced the Bracero 2.0 Act this summer, arguing it would provide essential support for Texas agriculture. However, Alvarado warns that the revival would replicate the harsh conditions faced by workers in the past.

“I remember being paid 45 cents an hour and working 14 hours a day, seven days a week,” Alvarado recounted. He vividly describes the grueling tests braceros endured, from blood tests to DDT dusting. “Those experiences were hard, and the Mexican bosses treated us like slaves,” he added, highlighting a troubling legacy of mistreatment.

The potential revival of the program has gained traction with remarks from Donald Trump, who recently acknowledged the labor crisis, stating, “We can’t let our farmers not have anybody.” However, Alvarado argues that current undocumented workers are already fulfilling those roles and deserve legal protections rather than replacement with new laborers.

While discussions continue, Alvarado remains skeptical. He emphasizes, “Why not let the people here stay? Deporting them is horrible.” His message resonates amid ongoing debates about immigration reform and labor rights.

The former bracero’s perspective is crucial as lawmakers consider the implications of a revived program. Many fear that history will repeat itself, leading to exploitation and a loss of rights for workers. As Alvarado poignantly stated, “They’ll come with no rights other than to come and get kicked out at the will of the government.”

Alvarado’s story is a powerful reminder of the human cost behind labor policies. His experiences serve as a warning against repeating the mistakes of the past, advocating instead for the rights and dignity of all workers. As the situation develops, it raises critical questions about the future of agricultural labor in America and the treatment of those who undertake it.

As the conversation continues, the urgency for humane solutions becomes increasingly clear. The potential consequences of a revived Bracero Program remain a pressing concern, and Alvarado’s voice adds a vital perspective to this ongoing debate.