The Museum of Art and Light in Manhattan, Kansas, is currently hosting an exhibition titled “Crafting Sanctuaries: Black Spaces of the Black Great Depression South.” This display seeks to reclaim and broaden the historical narrative surrounding the Great Depression, particularly emphasizing the experiences of Black Southerners. Established by the United States Department of Agriculture in 1937, the Farm Security Administration (FSA) aimed to provide assistance to rural communities grappling with economic hardship. Central to its mission was a photography project directed by government official Roy Stryker, which primarily showcased the lives of White families, thereby offering a limited view of rural America.

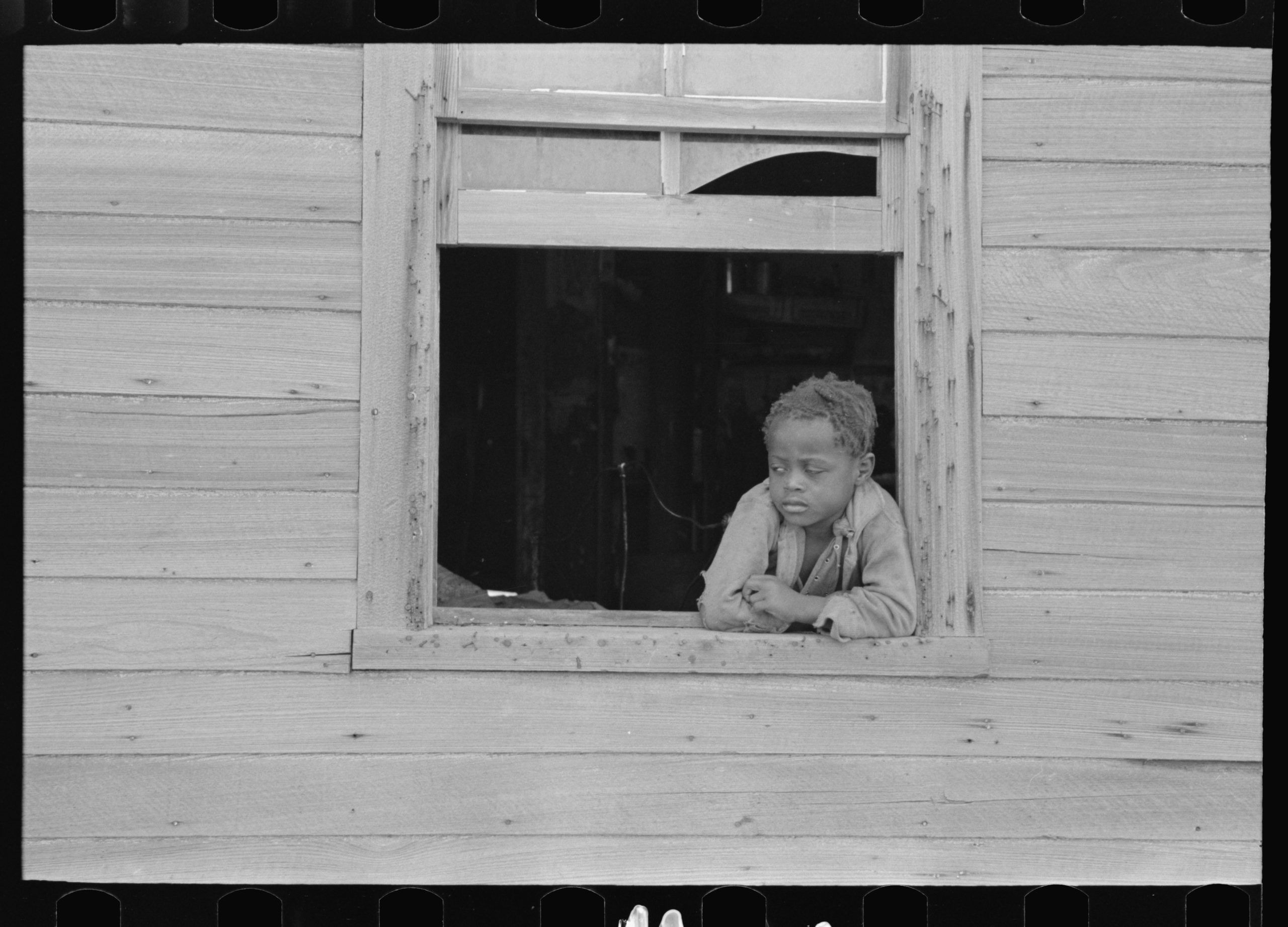

The current exhibition features a curated selection of photographs taken by notable photographers such as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and Russell Lee. These images highlight the intimate lives of Black individuals and families across six states: Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Florida, Mississippi, and Missouri. The exhibition, which runs through March 2024, is presented in collaboration with the Art Bridges Foundation and aims to illuminate the resilience and beauty found within Black communities during a time marked by economic distress and racial violence.

Curator Tamir Williams noted that the exhibition is a critical exploration of the absence of Black and other non-White individuals from the visual memory of the Great Depression. Williams, who was approached in the summer of 2023 to curate the project, was inspired by earlier works like Nicholas Natanson’s “The Black Image in the New Deal: The Politics of FSA Photography” and Sarah Boxer’s article “Whitewashing the Great Depression” in The Atlantic. Williams emphasized the need to address how this exclusion occurred and how it could be redressed through the exhibition.

During the curation process, Williams spent significant time at the Library of Congress examining the digital FSA collection. They were particularly drawn to images showcasing small homes constructed by both White and Black laborers, especially in La Forge, Missouri. This research motivated Williams to seek a more comprehensive understanding of Black life during this period.

The photographs selected for the exhibition are presented with reverence and care, offering glimpses of Black domesticity and community life. Associate curator Javier Rivero Ramos expressed admiration for Jack Delano’s photograph of a “Negro tenant family near Greensboro, Alabama” from 1941, describing it as a powerful capture of emotion and experience. Another notable image by Marion Post Wolcott features three children and a dog in their family home, encapsulating both the magical and mundane aspects of daily life.

In addition to “Crafting Sanctuaries,” the museum is showcasing “Sanctuary in Motion,” a companion installation developed with the Yuma Street Cultural Center. Kristy Peterson, vice president of Learning, Engagement, and Visitor Experiences at the museum, highlighted the significance of Manhattan’s history as a town founded by abolitionist settlers around 1855. This context enriches the understanding of the exhibition and its focus on community resilience.

Williams articulated their hope that the photographs would enable viewers to appreciate how Black Southerners crafted personal and communal sanctuaries during a challenging era. By showcasing the beauty and strength of these communities, the exhibition serves both as a corrective to historical narratives and as a meditation on the profound impact of space and community in the face of adversity.

As the exhibition continues to draw attention, it reflects a broader movement to re-examine and reclaim historical narratives that have often marginalized or overlooked significant contributions from diverse communities. The combination of powerful imagery and historical context invites viewers to engage with the past in a meaningful way, fostering a deeper understanding of the complexities of American history.