Family separation, often framed as a protective measure, poses significant harm to children’s mental health. It can lead to conditions such as PTSD, anxiety, and depression, ultimately affecting their life expectancy. Recent events have intensified scrutiny around the practices of child welfare, juvenile justice, and immigration enforcement, which commonly separate families under the pretext of safety. Mental health providers have been criticized for legitimizing these detentions by offering care in environments that can exacerbate psychological trauma.

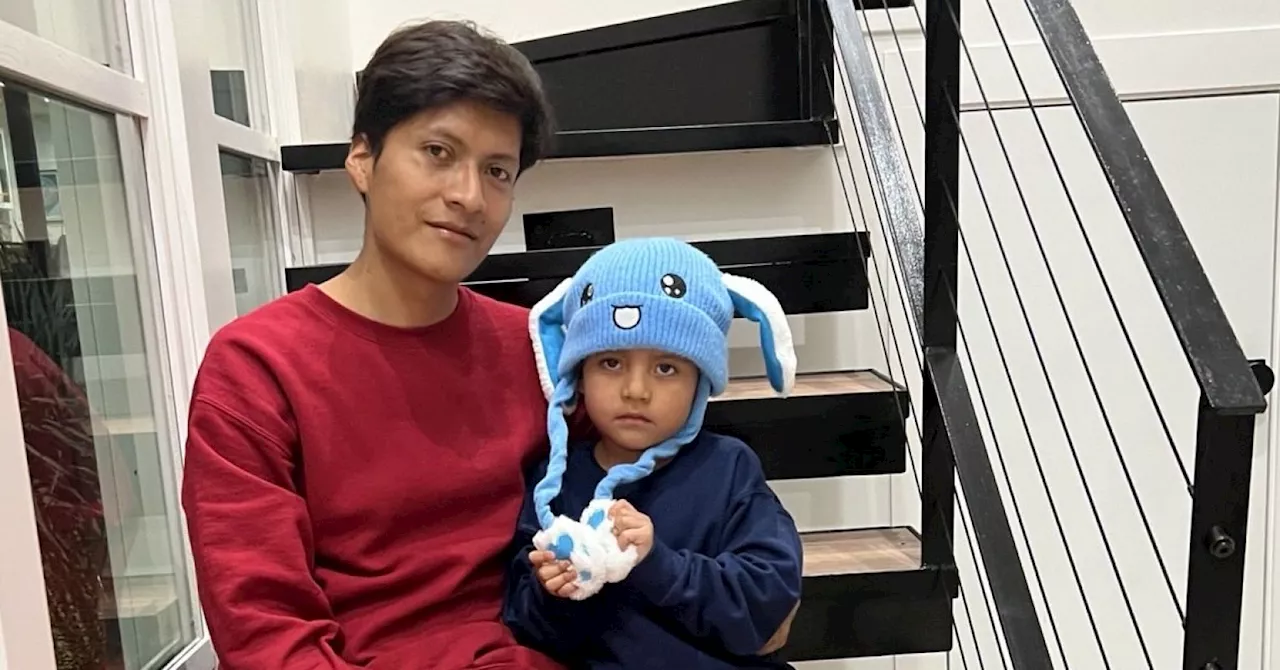

The case of Liam Conejo Ramos, a five-year-old boy apprehended by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) on January 20, 2026, highlights this alarming trend. Liam and his father were detained shortly after arriving home in a Minneapolis suburb, despite reportedly entering the United States legally in search of asylum. Their attorney maintains that their detention was unlawful, raising serious concerns about the treatment of families seeking refuge.

Witnessing children being forcibly separated from their families can devastate entire communities. Concerns over deportation can impede healthcare access and school attendance, compounding health and educational challenges. A tragic illustration of this was the case of a child who reportedly took her own life after classmates threatened to report her parents’ immigration status.

As a child psychiatrist committed to health equity, I recognize that the systemic nature of family separation extends beyond immigration enforcement. Child welfare and juvenile justice systems often employ similar tactics, removing families in the name of safety while perpetuating harm, particularly in Black and Brown communities. Numerous reports document the unjust removal of children from families, with poverty often mistaken for neglect.

Such practices have roots in historical injustices, including the transatlantic slave trade and the forced removal of Indigenous children to boarding schools. The field of mental health emerged in the mid-20th century from child guidance clinics, which often operated in tandem with juvenile courts. These clinics typically upheld white, middle-class ideals as the standard for health, marginalizing those from poorer or immigrant backgrounds.

Mental health professionals must confront their roles in enabling family separation. For instance, mandated reporting can inadvertently funnel families into welfare systems despite no evidence of abuse. Furthermore, diagnoses like oppositional defiant disorder can lead to criminalization, while treatment in psychiatric facilities can mask incarceration as care.

Once children enter state custody—through relinquishment, child welfare removal, or juvenile justice—they may face coercive psychiatric practices. Data indicates that children from racialized communities are more likely to be prescribed medications that do not address the underlying trauma caused by their detention.

Research in child welfare and juvenile detention often normalizes family separation by developing therapeutic interventions within systems that perpetuate toxic stress. A study highlighted that Black parents undergoing surveillance while receiving parenting training exhibited signs of depression. Rather than recognizing the damaging effects of this surveillance, researchers suggested adding depression treatment, reflecting a cycle of harmful logic.

Mental health providers might believe they are assisting those in need. However, this can inadvertently support the notion that healing is feasible while detained, contradicting established understanding of trauma and safety. Medicalizing predictable responses to confinement makes it difficult to question the validity of the detention itself.

Shifting the focus from viewing detention as a site of care to advocating for family unity is crucial. This means re-evaluating the role of mental health providers in preventing entry into detention, facilitating quicker releases, and funding support systems that make confinement unnecessary.

Redirecting substantial funding currently allocated to child detention systems could significantly improve outcomes. Programs such as California’s Differential Response and New York’s Family Assessment Response prioritize voluntary support over investigations, demonstrating a shift in approach that can mitigate the risk of abuse while reducing reliance on policing.

The mental health rights and recovery movements are already working to create community-based alternatives. Initiatives like peer respite centers prioritize care outside of locked facilities, emphasizing supportive relationships. Additionally, some states are closing juvenile detention facilities and expanding diversion programs that keep youth within their communities, illustrating that detention is a choice rather than a necessity.

In the days leading up to Liam Conejo Ramos’s release, disturbing footage showed children in detention facilities crying out for freedom. This serves as a poignant reminder that the psychological toll of family separation extends beyond immigration, affecting child welfare, juvenile justice, and psychiatric systems. It is imperative for mental health providers to acknowledge their complicity in these systems and redirect efforts towards maintaining family unity as a vital mental health intervention.

Withdrawing support from punitive settings and focusing on community resources and family preservation represents an ethical and clinical obligation that must be prioritized. True healing cannot occur in environments that enforce separation.